Cognitive Processing Skills Training

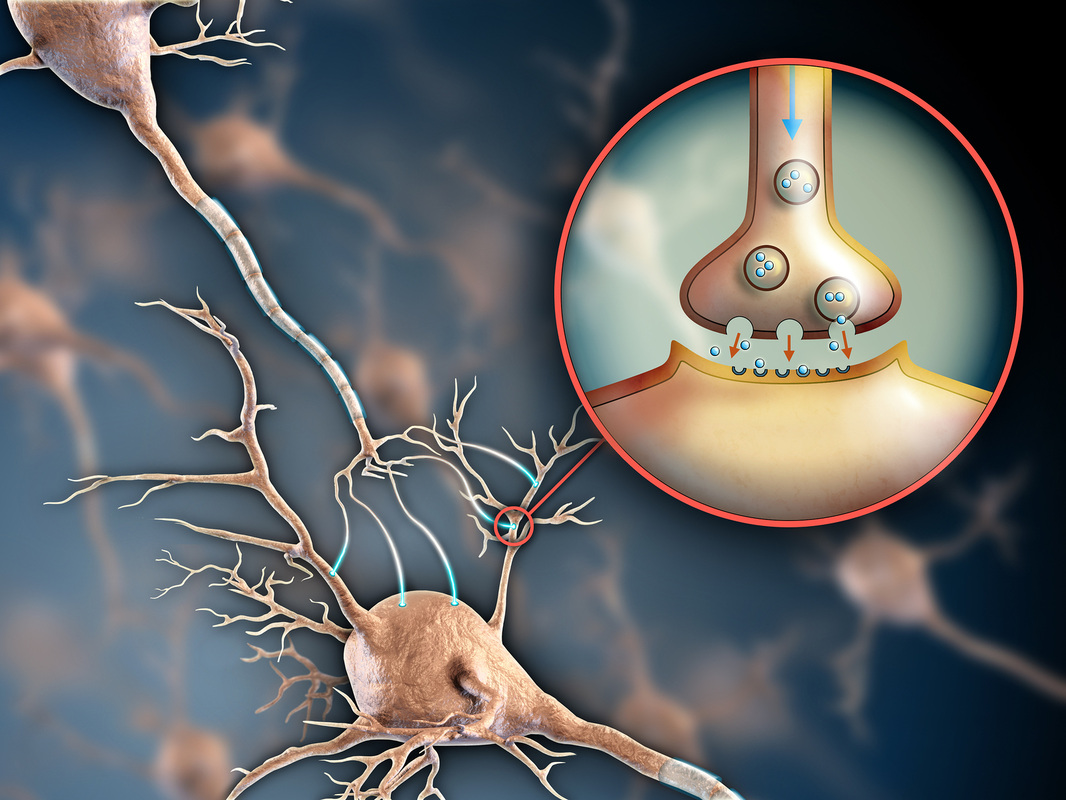

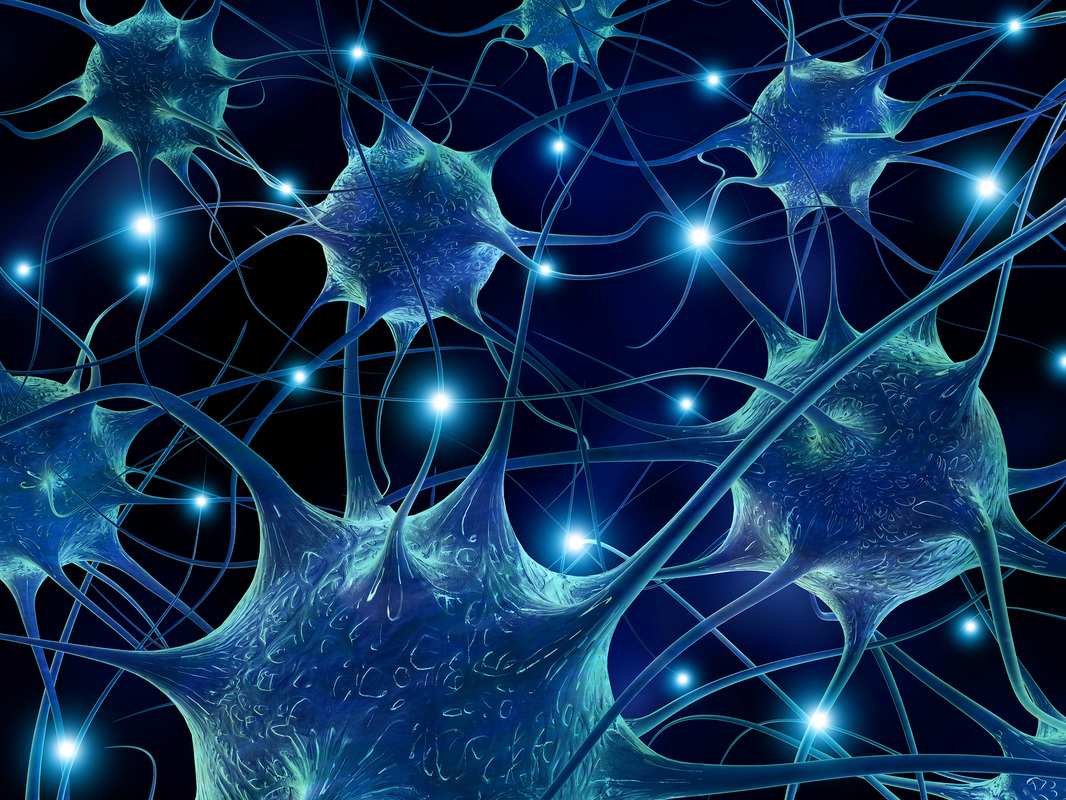

Background There are three major systems involved in learning: 1) sensory input system, 2) cognitive processing, and 3) learned skills or knowledge. Information must first get into the brain through the five senses. Information must be clear and orderly. If information cannot get into the brain, if it is distorted, or if it is jumbled, that can make learning difficult. Once information gets into the brain, the brain processes it in order to make sense of it. Multiple processing skills are used to make this happen. One must pay attention to capture the information, use visual or auditory processing skills to process the information, remember it, determine if action is required, and if so, what action and whether enough knowledge is available to make sense of the information. If there is sufficient knowledge, the proper actions can be taken. If there is insufficient knowledge, the brain must process the information further to learn. Logic and reasoning skills, executive function, working memory, etc. all come into play to make sense of the information and create knowledge. Repeating the process builds learned skills. We have to convert short-term memories into longer-term memories and have them ordered such that knowledge occurs. We build learned skills such as language and math. We learn how to tell time and tie our shoes. All three system have to work together to accomplish tasks and learn. Weak processing skills make learning harder and less efficient. In some cases, sufficiently weak skills may make learning almost impossible. Fortunately, the brain can adapt given the proper training. Brain training in essence takes place naturally. Most would agree that a ten-year old knows more and can do more than a two-year old, unless there has been an injury to the brain or unusual circumstances. How did that maturity and improvement in processing and learned skills happen? It happens through the natural course of exposure to stimuli, teaching and experimenting. The brain gets more powerful through use, similar to any muscle. A combination of genetics and life experience craft each person's ability to learn and their knowledge base. The period of development from womb to age five is a critical time to build effective neural connections and pathways that enable learning in school. In most cases, children who have been read to more, exposed to more positive stimuli, have been nurtured and challenged, will have strong cognitive processing skills. They will know more and be able to process information better than a child who heard much less language, played less, and was challenged less. In most schools, there is a five year gap or more in skills among the students entering kindergarten. Some students are three years behind and some students are up to two years ahead of grade level or more. Genetics does play an important role, but life experiences also have a major impact. Natural brain training has occurred to this point and will continue. However, a child who enters kindergarten behind likely has weaker cognitive processing skills than a child who is at grade level or above. Instruction for a child who is behind is generally not as effective as it is for a child who has stronger processing skills and more learned knowledge, e.g. more vocabulary. Just more instruction generally does not help a child who has weak processing skills. If they have sufficiently weak working memory, no amount of instruction solves that problem. If they have weak auditory processing skills, phonics does not make much sense to them. Students with weak processing skills require intensive, individual training to strengthen those skills. Even olympic athletes with natural talent have to train intensively to win. Training is different than instruction. Why train the Brain? As noted above, brain training takes place naturally. It is not something new. However, if a student enters school with any relatively weak processing skills, those skills generally will not improve under traditional instruction. Weak skills make learning difficult. So the obvious solution is to have the student do the proper brain training to strengthen weak skills so learning is easier, faster, and more effective. A reasonably strong body of published research has proven that cognitive skills can be improved through the proper training. A very good website that provides a wealth of information is Sharp Brains. Who should do the training? Everyone can benefit from brain training. Those with relatively weak skills can benefit the most. However, even top athletes still train to maintain their skills and gain a competitive advantage. The same with top learners. Parents can engage their children in age-appropriate activities from an early age on. Formal brain training from an intervention perspective typically does not come to mind until parents realize that their child appears to be behind. Computerized brain training can begin with some activities as early as five or six, but serious training generally is not recommended until at least age 7. Students of all ages can benefit from brain training. Various studies have shown that cognitive skills generally improve naturally until about age 30, then tend to decrease thereafter. However, focused training can keep skills at higher levels for some time. Older people tend to notice a slowing down of their skills at some point, but remaining active, learning new things, and challenging the brain with the right activities can help to keep the mind sharp in most cases. How is the training done? The best form of training is provided by professional trainers one-on-one. However, this type of training can be relatively expensive and many do not have access to a trainer. For those, online training and purchasing the right games can be a valid alternative. Just do a Google search on brain training and you should find many alternatives. There are even a lot of online brain training games for free. However, please don't think that these online exercises are a silver bullet. To see any serious results a person must train consistently and intensively. The training needs to be comprehensive and challenge the brain in such a manner that the skill is actually improved. The training needs to be challenging but not too hard and prove the right sequencing. Various online training programs make various claims, but our experience is that a person needs to train a minimum of 30 minutes per day, 4-5 days per week for at least 12 weeks. Many students will need double or triple that time to really make a difference. The Sharp Brains link above has several articles describing what works. What kinds of improvement are possible and how long does it take? The kind of improvement depends upon the beginning skill levels, what training is done, and how consistently and intensively the training is done. It also depends upon whether there are any underlying physiological issues that may be impacting the student. If a student has sufficiently weak cognitive skills that make learning difficult, slow, or even nearly impossible, in most cases the right training can help that student improve to the point that there is a noticeable difference in their ability to learn. Each person and each situation may yield different results, but in general, the right brain training can make a difference. As noted above, it will take a minimum of a month, probably two months of the right training before you can really measure the improvement. But, it will really take 3-6 months to do it right. One teacher was supervising students doing our training and she noticed that she may have some weak skills. She was working on a master's degree and found that it was taking her about ten hours a week to do a typical paper for her classes. She wondered if the training could help her. She began the training at home at night and found it challenging. She said she noticed a difference after about a month, but after two months she really noticed a difference. That same paper that previously had taken ten hours was now only taking two hours to complete. She did not have to re-read the research materials multiple times. Once was enough. Before she could not settle on the topic and get started without going back and forth several times. She had many false starts because she just could not organize the materials in her head to provide a clear direction. After the training, she said she knew better and faster what she wanted to convey and just wrote the paper. Not everyone will have that kind of improvement. And remember, this person had succeeded in college and received a bachelor's degree. She was also a successful teacher. However, she had been compensating for some weak skills which made learning harder and slower. But, with persistence she had succeeded. The training took her to a new level where she was able to better focus, remember, and function more effectively. Do the improvements last? Some training focuses too narrowly. A student does get better, but really only better at doing the game. It does not translate into improving learning overall. The training may not strengthen all of the weak skills and thereby there is still something that is holding the student back from achieving their full potential. The right training can strengthen all of the core skills and unlock a student's learning potential. Once that breakthrough has occurred, the student operates on a different level. Similar to learning how to ride a bike, you might get a little rusty if you don't ride enough to keep up the skill, but unless there has been a physiological change, most people remember how to ride a bike forever. The key point is that if you continue to study and learn, you will continue to exercise and strengthen your cognitive skills. By continuing to use your cognitive skills the improvements will last. The specific measurement of a given cognitive skill may peak during the training and taper off if the training is not maintained similar to athletic performance. However, the improvement in learning should not go away. Keep in mind that we all will likely loose some cognitive skill proficiency as we age. But, the improvements in learning and focus that the right training can effect should continue as long as there is no physiological issue and the person remains active in learning. What proof is available that it works? For me, I have seen the positive change time and time again. I don't need a peer-reviewed article with tons of research and charts to prove anything to me. Don't get me wrong, research is important. But, many of the instructional techniques and curricula in schools today either have no research backing it, yet it is used, or it does have evidence-based research, yet it is not solving the need. A good research for information is the Sharp Brains site. How do I determine the best program? If you can find the right clinical training program with one-on-one training and you can afford it, that is likely the best option. An example of one we recommend is LearningRx. I have personally seen their program work wonders with children I know. There may be others out there. There are activities and games available for free or at a reasonable cost that can help. LearningRx has a site that offers great advice and examples of free activities, Unlock the Einstein Inside. The Sharp Brains site also has some information. just do a Google search on free brain training and you should find lots of resources. However, to really see progress, you need to find a program that is comprehensive and follow through properly on the training. The Sharp Brain site lists hundreds of programs and they provide a top list. One thing we have learned is that often students who struggle with learning also have self esteem and mindset issues. I recommend reading the book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck. |

|

|

Copyright 2014-21 CogRead LLC, all rights reserved

Proudly powered by Weebly